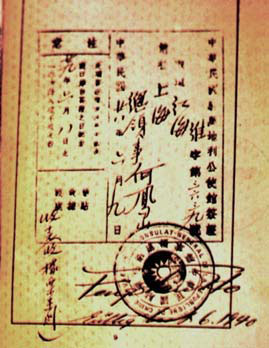

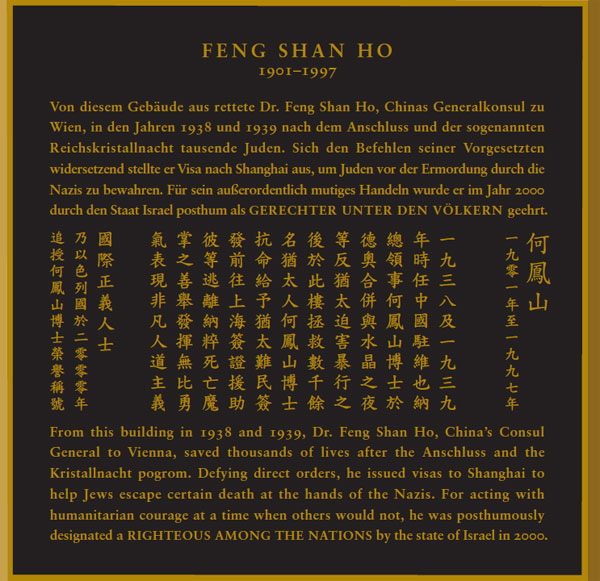

Plaque in Vienna commemorates Feng Shan Ho's heroic deeds On April 21, a bronze plaque was unveiled in Vienna, Austria to commemorate the heroism of a Chinese diplomat more than seven decades ago. Feng Shan Ho, Chinese consul general to Vienna from 1938 to 1940, was one of the first foreign diplomats to save Jews from the Holocaust in Nazi-occupied Europe. It was only after his death in 1997 that the story of his humanitarian feat - buried for six decades - finally came to light. In July 2000, Israel bestowed the title of Righteous Among the Nations, one of its highest honors, on Ho "for his humanitarian courage" in the rescue of Jews. From left: Hu Bin, counselor from the Permanent Mission of China to the UN in Vienna; Ambassador Zvi Heifetz of Israel; Ambassador Zhao Bin of China; Manli Ho; and Hu Lian, head of the special delegation from Yiyang, Hunan province. Provided to China Daily For the 65 people gathered at the Ritz Carlton Hotel in Vienna, this was an unprecedented historic event: to publicly recognize a Chinese native for contributions in the European Theater of World War II during this 70th anniversary year of the end of the war. But for me, it was much more than that. Feng Shan Ho was my father. In the brilliant sunshine of a spring morning in Vienna, I joined Ambassador Zvi Heifetz of Israel, Ambassador Zhao Bin of China, a special delegation from my father's hometown of Yiyang in China's Hunan province, academics and leaders of the Jewish and Chinese communities to unveil a tri-lingual commemorative plaque in German, Chinese, and English at the site of the former Chinese consulate general in Vienna, now part of the Ritz Carlton Hotel. It was from this location, following the Anschluss, or union of Germany and Austria in March 1938, that my father began issuing visas to the Chinese port city of Shanghai, helping thousands of Jews escape from the Nazis. However, the impact of my father's actions extended well beyond Austria and the recipients of his visas; he put Shanghai on the map and into the consciousness of Jews in Nazi-occupied territories as a refuge of last resort. As a result, from 1938 to 1940, about 18,000 European Jewish refugees fled to Shanghai, escaping almost certain death at the hands of the Nazis. Yet during my father's lifetime, not even we, his family, realized the full scope of what he had done. It was only after his death that I began by chance to uncover my father's deeds. Trying to retrace this history more than six decades later, however, was like looking for a pebble in the ocean. We shall never learn the full extent of my father's humanitarian efforts. There was no "Schindler's List" of names. After the war, the survivors had scattered all over the world. Most of the adults who lined up in front of the Chinese consulate to obtain visas were gone, and did not necessarily tell their children the details of how the family escaped. At the end of World War II, China was plunged into a civil war. There were few Chinese archival documents left to be found. Nevertheless, I doggedly looked for survivors and painstakingly scoured archives in Washington DC, Vienna and Israel. Little by little, through sheer persistence and serendipity, I was able to fill in much of the history piece by piece. Posted to Vienna, Austria in 1937, my father was appointed China's consul general in April 1938, one month after the Anschluss. He witnessed the reign of terror that was unleashed against Jews following the Nazi takeover. Many Jews from Austria and Germany tried to emigrate, but found almost no country willing to allow them entry. Their plight was further exacerbated by the July 13, 1938 resolution of the Evian Conference, which made it evident that almost none of the 32 participating nations was willing to accept Jewish refugees. To force Jews to emigrate, the Nazis instituted methods combining coerced expulsion and economic expropriation. Nazi authorities told Jews that if they showed proof of emigration - such as an entry visa with an end destination - they, as well as relatives deported to concentration camps, would be allowed to leave. In his memoir, Forty Years of My Diplomatic Life, my father would later write: "Since the Anschluss, the persecution of Jews by Hitler's 'devils' became increasingly fierceI spared no effort in using any means possible to help, thus saving countless Jews!" But unlike his fellow diplomats, my father faced a unique dilemma at that time: Most of his home country and all its ports of entry had been occupied by the Japanese since 1937. Any document or entry visa issued by a Chinese diplomat would certainly not be recognized by the Japanese occupiers. In order to help Jewish refugees, my father came up with an ingenious way to use an entry visa as a means of exit or escape. His entry visas were issued to only one end destination - Shanghai. The Shanghai visas would provide Jewish refugees in Austria with the proof of emigration required by the Nazis to leave. Practicing what he called a "liberal policy", my father authorized the issuing of visas to any and all who asked. Armed with a Shanghai end destination visa, Jews could then obtain transit visas to escape to other countries. "I knew that the visas were to Shanghai 'in name' only", my father would later recall. "In reality, they provided a means for Austrian Jews to find a way to get to the United States, England or other preferred destinations." Many Jews were also released from the concentration camps of Dachau and Buchenwald on the strength of these Shanghai visas. Shanghai itself, however, required no entry papers. In 1937, the city had fallen into the hands of the Japanese. The Chinese Nationalist government had retreated to Chongqing, leaving Shanghai harbor wide open, without passport control or immigration. As a result, anyone could land without papers. In making Shanghai an end destination, my father provided a failsafe to refugees not able to land elsewhere. Word spread quickly to Jews in other Nazi-occupied territories that in China there existed a refuge which required no entry papers. That is the reason that the majority of the 18,000 Jewish refugees who ended up in Shanghai were from Germany, not Austria. Most of the Austrian Jews who were able to obtain visas from my father's consulate used them as a means to escape elsewhere - Cuba, the Philippines, England, North and South America and Palestine. The first visa recipient I tracked down was the late Eric Goldstaub of Toronto, who did go to Shanghai. Goldstaub recalled that he visited 50 foreign consulates in Vienna before obtaining 20 visas from the Chinese consulate. It was to a place, Goldstaub recounted, most Austrian Jews had never even heard of, much less dreamt of going to. When the anti-Jewish pogrom known as Kristallnacht erupted in Germany and Austria on November 9-10, 1938, both Goldstaub and his father were arrested and imprisoned, but with the Shanghai visas as proof of emigration, they were released within days and embarked on their journey to Shanghai. On Kristallnacht, my father himself faced down the Gestapo at gunpoint to help his Jewish friends, the Rosenbergs, to whom he had issued visas to Shanghai. He had come to their home to see them off. Because of my father's intervention, Mr. Rosenberg was released from detention, and the family was able to leave Vienna safely for Shanghai. Other families, such as that of Karl Lang, did not have such personal intervention on Kristallnacht. Lang's daughters, Marion Alflen and Susie Margalit, recalled later that their father was arrested and deported to Dachau concentration camp. He was released only after their mother was able to obtain a Shanghai visa and present it to Nazi authorities as proof of emigration. The Lang family left Austria for England and then made their way to the United States. A visa to Shanghai. In the meantime, Chen Jie, the Chinese ambassador to Berlin and my father's direct superior, was concerned that my father's issuance of visas on such a large scale would damage Sino-German relations. He ordered my father to desist, but my father disobeyed the order and continued to issue visas. My father was later punished for his disobedience, receiving a demerit in his record. In early 1939, the consulate's building - on which the plaque was placed in his honor last month - was confiscated by the Nazis and my father was forced to relocate to smaller quarters at his own expense. One question I am often asked is how many visas were issued and how many lives were saved under my father's watch. After more than seven decades, there is no way of finding exact figures. The best that can be determined now is that the visas numbered in the thousands. Based on the highest serial numbers of visas that I have found, close to 4,000 were issued about a year after the Anschluss. How many more were issued in the remaining months before the outbreak of World War II on Sept 1, 1939, when routes of escape began to shut down, is difficult to determine now. The only surviving Chinese documentation I have found indicates that the Chinese consulate in Vienna issued an average of 500 visas a month to Jews in the nearly two years after the Anschluss. I have also uncovered evidence that in addition to visas, my father issued affidavits and other documents to help Jews escape. As to how many lives were saved, even my father himself never knew. One visa sometimes served an entire family. My father was never reunited with any of those he had helped. The majority of them never even knew his name. Another question that I am often asked is: Why would a man from China save Jews in Europe when others would not? My immediate answer is that if you knew my father, you would not need to ask, but of course that is no longer possible. What he did was totally in character. He was a man of conscience and courage with a compassionate heart. My father's own explanation for what he did was simply this: "On seeing the Jews so doomed, it was only natural to feel deep compassion, and from a humanitarian standpoint, to be impelled to help them." Another reason that would have propelled my father to extend his hand to Jews is that he came from a generation of Chinese who felt that China had been humiliated and persecuted by 100 years of foreign imperialism. In fighting Japanese aggression, this generation was determined not to allow that humiliation to continue. In that sense my father was very sensitive to persecution and to bullying of any peoples. My father was born into poverty in rural China. Academically brilliant, he obtained a doctorate in 1932 from the University of Munich, where he witnessed the rise of Adolf Hitler. In 1935, he joined the Chinese Foreign Service and served for nearly 40 years before retiring to San Francisco, California. Ten years after his death in 1997, in accordance with his wishes, I took his and my mother's ashes back to China to be buried in his beloved hometown of Yiyang. When I began this search nearly 18 years ago, I never imagined that it would keep unfolding as it has. As I waded deeper into these uncharted waters, the story became panoramic and grew to encompass the hitherto unchronicled history of escape from a genocide in Europe, and revealed how one person's actions led to the creation of a refuge on the other side of the world - in China. Uncovering this history has been my greatest feat as a journalist. I had to master the very complex and turbulent history and politics of both China and Europe during that era, because I feel a responsibility not just to my father, but to the survivors and to history to record it accurately. What my father did in those two short years in Vienna has to be placed in a much larger context, which is the interplay of Chinese and Western history in the 20th century. And this commemorative plaque, which took five years of effort to bring to fruition, is a first step toward that end. homanli@chinadaily.com.cn Feng Shan Ho and his daughter Manli Ho in 1977. Photos Provided by Manli Ho / China Daily The bronze plaque unveiled in Vienna to commemorate Feng Shan Ho.

Chinese diplomat honored for saving thousands of Jews

Editor:李莎宁

Source:红网综合

Updated:2015-05-18 16:22:09

Source:红网综合

Updated:2015-05-18 16:22:09

Special

Contact

Welcome to English Channel! Any suggestion, welcome.Tel:0731-82965627

lisl@rednet.cn

zhouqian@rednet.cn