As her daily routine begins, Xu Hui walks past the debris of demolished homes in a shantytown in Changde, Hunan province, her mission being to ask people living in the area whether they are willing to move away from it.

Xu expects that once generous compensation is dangled before them, her interviewees are likely to jump at the chance to move away from the area, notorious for its human congestion and filth. Yet running against that expectation is the fact that nearly all of the 200 families or so whose homes are due to be next on the chopping block have chosen to stay and buy the new houses that will be built in their place.

Xu attributes this change of heart among locals about where they live to an art show in a newly built art center in the shantytown in September. On display were works by artists in an art project aimed at helping preserve the collective memory of the area, where the locals have lived for decades. Many of the artworks will eventually be placed in public spaces established in the area once the new houses are built.

The shantytown on the right bank of Changde's Yuanshui River in Hunan province will be demolished and replaced by new housing in six to eight years. Photos Provided to China Daily

"When people saw the show and the fancy art center, they were dumbstruck," says Xu, 40, who has lived in the shantytown for more than 10 years and works for a local community committee. "They then began telling me that they wanted to stay."

Like most residents living in Changde, a prefecture-level city with a population of 5.7 million, Xu had previously had little interest in art, something she equated to local operas or square dancing, a popular pastime throughout China.

Winding through the city is the Yuanshui River, on one bank of which is a well-off area that has flourished over the past 10 years as a result of urbanization. The other side of the river has not fared nearly as well, and it is there that the shantytown sits. As the disparity between the two sides of the river became ever more apparent, the local government decided to act last year, and it is as a result of this that the shantytown area is being rebuilt from the ground up.

"Urbanization in China is advancing at an incredible pace, and old buildings make way for new ones every day," says Hu Quanchun, a sculptor who specializes in public works. "But making art a part of the process of urbanization is rare."

Hu says that when he visited Changde to take part in a one-month residential art project in March and April, he had barely any idea about how to get started. For him, the area seemed to be much like any other small city in China, with rows of apartments and two-storey houses, narrow alleys and a lot of debris lying everywhere, the remnants of demolished houses.

Working under Hu is a team of 14, most of them students at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. They lived with local families and got to know the locals well.

After several days getting to know the locals, Hu decided to create pieces of art that related to their daily lives, the aim being to help safeguard the collective memory.

Hu and his team found hundreds of discarded metal plates in the debris of demolished homes. These plates resemble car license plates bearing street and apartment numbers.

It is hardly surprising that because of the shantytown's location, it used to be a fishing village, and a celebrated Chinese writer, Shen Congwen, once wrote an essay that evoked how the countless boats and ships nestling there reflected the area's prosperity. These days the fishermen have all but disappeared, and most of the locals work in a commodity market nearby.

So Hu decided to attach the plates to a wooden fishing vessel that used to be a common sight in the area. When locals saw the boat decorated with the plates that identified their neighbors, they approached Hu and asked him whether he could do a similar artwork involving their houses.

Their eagerness to be involved was also fired by another of Hu's works, a concrete cube made of construction waste collected from a family's home with their address on it. A family's old furniture, as well as other items discarded as they moved out of their old home, can also be made part of the cubes.

"When people build a house and make it their home, all sorts of materials particular to them go into it," Hu says. "House owners build up their homes with different materials. So the cube represents the unique memory of a family."

Many residents have asked him to create a cube for them, he says. Previously they just seemed curious about what his job was and were confounded by his interest in collecting waste.

These cubes will later be used as stools in public spaces in the area, recounting in their special way the history of the old shantytown.

"What I appreciate about this is that people will recognize themselves and their past when they see these stools, instead of simply erasing the past when a new town is set up," Hu says.

His team also collected bricks in ruins to engrave people's wishes on them and build them into a memorial wall.

"The locals are very down-to-earth people. They'll say straight out, 'I want to make a fortune'," Hu says with a laugh. "Some write poems."

Another artist, Zhao Ming, focuses more on the emotions of people, doing so by using pictures and sound. Zhao and her team are from the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province. They spent a busy week in the shantytown, mainly recording sounds, including voices. These included people chatting, peddlers hawking their wares, riding scooters, dogs barking and the hum of insects in vegetable gardens. They also came across a local opera society in a teahouse and recorded what Zhao calls "the voices of art".

"Life here is very slow and easy. In fact, people here don't seem to be as driven with lust as big-city folk are."

Zhao reckons that those who inhabit the shantytown are mainly children, middle-aged or older people. Young people seem to prefer living on the other bank, where the downtown area is, she says.

She and her team set up an open sitting room beside the Yuanshui River against a ruined house, complete with discarded furniture in which they planted audio devices. Then they invited locals to the sitting room and chatted away as the background sounds added an air of everyday life to the proceedings.

"They needed some coaxing to come here, but now people are making frequent visits and say how much they love the place."

Xu, whose house is one of those that has already bitten the dust, says she could never have imagined that she would miss what used to go on every day in this place and, through the artists, she is being given the chance to satisfy her nostalgic longings.

Like many of her neighbors who have chosen to stay, Xu rents an apartment nearby, waiting eagerly to see her new home.

The sound installation with photos is now on display in the newly built art center, the first building to set up in the shantytown.

Zhao says it is rare for artists to take part in pulling down the old and raising up the new, and she plans to return to Changde to do more artworks next month.

"When people have everything they want materially, they naturally yearn for spiritual things," says Zhao of locals choosing to stay instead of moving to the supposedly better section of town on the other side of the river.

Altogether, more than 2,500 buildings and houses will be removed in the shantytown, involving 8,612 families, the local government says. The project is expected to take six to eight years to complete.

Zhao says she arrived in Changde in March, just after demolition had begun. Many people were on edge about what was happening around them and apprehensive about the future, she says. Most of the first group of families whose houses were demolished chose to move to other areas. But once the art project was finished and the show in the art center had opened, an increasing number decided to stay, keen not to let their memories, now embodied in art, simply die.

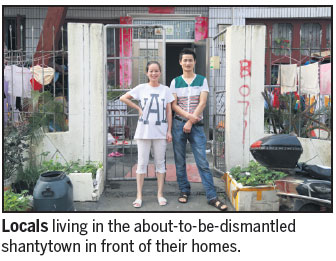

A local art group, Hummingbird, also took part in the project, collecting old furniture thrown out during demolition work, taking photos of families standing in front of their about-to-be-demolished houses and filming short stories about locals.

Zhong Jihong, a member of the group, says that several months after the group took pictures of one couple, the woman died, leaving her husband with a treasured last picture of them together. After a pregnant woman was being pictured as she left her house for the last time, she gave birth.

"This is not just about pulling down houses and putting up new ones, but about learning to take care of the people who live in them," Zhong says.

The long-term art project was set up by Changde Konland Urban Development Co, a State-owned enterprise that is working with the local government to develop the poor bank area.

Liu Hui, general manager of Changde Konland, says: "As China's urbanization continues apace, it's common to simply plonk down new buildings where the old ones once stood. We want to avoid that. We are thinking about what should be kept and why."

Over the past few decades, China's urbanization has gone through two phases, he says. The first was cities concentrating on building big factories and State-owned businesses. After 2000, cities set up lots of industrial zones.

"We have adopted an approach in which cities put a premium on culture, art and nature."

From the rubble, art and new life spring

Editor:张焕勤

Source:中国日报

Updated:2017-11-13 09:34:38

Source:中国日报

Updated:2017-11-13 09:34:38

Special

Contact

Welcome to English Channel! Any suggestion, welcome.Tel:0731-82965627

lisl@rednet.cn

zhouqian@rednet.cn