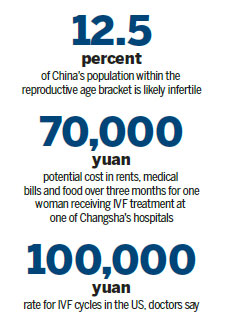

Lu Guangxiu, a veteran gynecologist from Reproductive and Genetic Hospital Citic Xiangya, Changsha.[Photo by Zhang Wei / China Daily] Assessing the popularity of assisted reproduction in China at a time of policy easing The alleyways off Xiang Ya Road in Hunan's capital, Changsha, are lined with rows of houses that have common kitchens and bathrooms but separate rooms. Couples from different parts of the province and elsewhere on the Chinese mainland arrive here daily in the hope of becoming parents. Inside the so-called small hotels, numbering in their hundreds, the wallpapers come more in blue than pink - representing the clich colors for boys and girls worldwide. The couples rent the rooms at an average cost of 1,200 yuan ($188.28) a month and visit a bunch of hospitals in the area, including banks that preserve sperms and embryos in liquid nitrogen. The facilities have turned this city in Central China into a major destination for assisted reproduction outside of Beijing and Shanghai. Recent interviews in Changsha and Beijing with many senior doctors, people opting for medical intervention to have children, practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine and a population expert suggest that assisted reproduction continues to be popular in China since the country's first baby through in vitro fertilization in 1988. While some interviewees say as China loosens its family planning policy, assisted reproduction may rise in relevance, others point to levels of infertility in present-day Chinese society as a reason for the sustained draw of IVF, intrauterine insemination and other forms of laboratory-enabled childbearing. On Oct 29, the Communist Party of China announced an end to the decades-long one-child policy, saying all couples could have two children in the times ahead. The rule change is expected to balance demographics, particularly with regard to the challenges posed by an aging society. People wait in the outpatient hall at a Beijing hospital for women and children, the hospital says its patient intake doubled this year. [Tian Baoxi / For China Daily] The policy easing started in late 2013, when couples with one parent as the only child, were told they could apply for permission to have second children in parts of China. By April, nearly 67,000 "second-child procreation certificates" were issued by the local government in Hunan, accounting for a quarter of 270,000 couples with one parent as the only child in the province, according to Changsha Evening News, a city-based paper. With 30,000 new babies born as a result, Hunan's birthrate increased by six percent this year, the report said last month. Local family planning officials weren't available for comments to this newspaper. There were around 17 million live births in China last year. And, with the nationwide two-child policy in place, the country could expect an additional 3 million babies to be born in the next five years, according to the central government. When Zheng Mengzhu, China's first IVF baby was born in Peking University No 3 Hospital, her parents who are from Northwest China's Gansu province, paid up to 4,000 yuan for more than a year's stay in Beijing, she says. The expenses were incurred on renting accommodation and paying hospital fees. Today, the same hospital charges an average of 30,000 yuan for an IVF cycle comprising a few sittings. When the "test-tube baby" program was launched in the 1980s, there were a handful of couples who showed up for it. Since then, the hospital has witnessed more than 10,000 assisted births. A woman seeking to have a baby through in vitro fertilization in the same city.[Photo by Zhang Wei / China Daily] Pregnancy watch In one of Changsha's quiet backstreets, a 35-year-old woman from Yongzhou, a city in the province's south, says she is pregnant with a second child after having failed to conceive through two previous attempts at IVF. Her first child is seven years old and was born without medical help. Married for eight years, she is from a business family. Hers was a problem common among infertile women: blockages in the fallopian tubes. The tubes connect the ovaries to the uterus, or womb as it is known in layman's term. Doctors also cite habitual abortions as a major trigger for infertility among Chinese women in the recent times. In the '80s, pelvic tuberculosis was a big culprit, they say. "My fertility problems started after my first child was born," Jian says, giving a lone name to guard her privacy. "I need to stay here for a month before going back home to ensure that all's well with my pregnancy." Although China has had a long and successful association with assisted reproduction, many remain sensitive to the topic and prefer to share just their surnames. A block from Jian's rented house, Liu, 35, and Su, 28, two women from the respective towns of Changda and Yiyang in Hunan, are seen watching a show on a video streaming website while sharing a meal of fish. A branch of Yangtze, the Xiang River flows through Changsha providing the city with fish and a pretty night view. Liu has taken an indefinite leave from her job at a polytechnic institute in order to pursue her IVF cycles in one of Changsha's hospitals. Following a few useless trails, Liu is finally pregnant but her return home will depend on the successful completion of her first trimester. Sperms preserved inside cans of liquid nitrogen at Lu’s hospital. [Photo by Zhang Wei / China Daily] She is likely to spend more than 70,000 yuan in rents, medical bills and food in the three months. For example, procedures such as egg extractions from a woman's ovary can cost up to 30,000 yuan. The mixing of eggs and sperms in a laboratory thereafter hikes the bill. But Chinese doctors argue that rates at more than 100,000 yuan for IVF cycles in the United States are still higher than China. "My parents worry I may not have a baby if I wait longer," says Su. She is among the younger enrollees for the assisted programs, but after her marriage of four years she is faced with social pressure to have a child. Unlike Jian and Liu, who came unaccompanied by their respective husbands to Changsha, Su's husband is by her side. Of the 90 million Chinese women able to now have second children if they wanted, half are between the ages of 40 and 49, the central government estimates. In its latest report, the China Population Association said 12.5 percent of the country's population - within the reproductive age bracket - is likely infertile. The percentage, four times higher than two decades ago, translated to about 40 million individual cases. The conventional international approach on reproductive populations is to look at people from ages 15 to 50, but doctors in China as in many other parts of the world, say it isn't easy to precisely measure infertility rates as the calculations are complex involving a host of factors from social to environmental. Women get their blood pressure measured before entering the chambers for doctors at a Beijing hospital. [Tian Baoxi / For China Daily] A World Health Organization study in 2010 found 48.5 million couples worldwide unable to have a child after five years of trying to have one. "China has average infertility when compared with world figures," says Liu Ping, deputy director, Center of Reproductive Medicine, Peking University No 3 Hospital. The 56-year-old gynecologist was on the team of doctors credited with Zheng's birth in 1988. In China, from 40 to 50 percent of infertility cases report problems with females, between 30 and 40 percent with males and from 10 to 20 percent with both, she says. The common fertility issues for women relate to uterine disorders such as endometriosis and polycystic ovarian syndrome, and for men, they are mainly about sperm count, quality and mortality. Including TCM Back in Changsha at the Xiangya Hospital of South Central University, a top medical institution in Hunan, the waiting halls are packed with men and women. Among them is a man who works in Shanghai's financial world. He says his sperm count has been falling despite fertility treatments for the past two years. Kuang Jilin, head, Hunan Provincial TCM Hospital in Changsha.[Photo by Zhang Wei / China Daily] He has made a few trips to Changsha so far, staying in hotels for brief periods. But Zeng, 33, isn't willing to give up. Married for a few years now, he and his 27-year-old wife are stressed because they don't have a child. "It has impacted our lives," he says, adding that friends from his hometown Yongzhou who had children through IVF told him about this hospital. He also says he isn't uncomfortable to talk about his treatment. "Male infertility is a common thing." Zeng says he has been seeing TCM practitioners as well. And, he isn't alone in his parallel pursuit of Western and traditional medicine. Although the approaches are remarkably different - TCM largely relies on the use of herbs and acupressure - many Chinese prefer to use both streams of medicine to tackle fertility issues as some interviews suggest. "More than 80 percent of Chinese women tend to accept TCM treatment for infertility, including those that are undergoing treatment under the Western system," says Teng Xiuxiang, 51, director, department of gynecology, Beijing Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Qiang Han, a 33-year-old male practitioner of TCM from the same hospital, says these days, Chinese men are becoming fathers only after turning 30. At which point, their sperm quality begins to fall. A sedentary lifestyle and staying up late may also affect male fertility. "I don't know if that man is still alive, but his child surely is," the veteran gynecologist says. Through their research, they can help families better understand the risks of diseases, she adds. China had very few hospitals that specialized in IVF until 2000. After the rules for the sector were set two years later, more units came up. Now, a total of 356 hospitals and clinics are licensed on the mainland to provide assisted reproduction, says the Health and Family Planning Commission. But will more middle-aged Chinese take to assisted reproduction with the two-child policy underway? Chen Wei, a professor of Sociology and Population Studies at Renmin University of China, says such techniques have already played an important role in helping couples become parents in the big cities. Analyzing fertility rates of the past decades, he expects the new policy to create a "small baby boom" from 2017 to 2019. That may happen with or without assisted reproduction. Feng Zhiwei, Wen Xinzheng, Yang Wanli, Luan Shu, Tian Yuan and Liu Zhihua contributed to this story.

Lu Guangxiu, a veteran gynecologist from Xiangya

Editor:李莎宁

Source:中国日报网

Updated:2015-11-16 09:52:40

Source:中国日报网

Updated:2015-11-16 09:52:40

Special

Contact

Welcome to English Channel! Any suggestion, welcome.Tel:0731-82965627

lisl@rednet.cn

zhouqian@rednet.cn